This Week in Sustainability

Historians will reflect a lot on 2020, a period that’s testing, and in many cases, brazenly overturning our social systems, values, and safety nets. It’s a sad, difficult time - but also one we hope serves as a true wake up call and catalyst for positive change, particularly sustainable decision-making and investment in the broadest sense of the word.

From an economics and labor perspective, we’ve also clearly been pushed into the era of remote work - the future that became our present. The productivity frontier turned living room norm.

As a result, our study methodology isn't completely free of self-reporting, survivorship, and other selection bias, given that website copywriting and directory listings can be incorrect, incomplete, or misleading. Nonetheless, we're cautiously optimistic our data set, in aggregate, paints a directionally correct assessment of today's startup reality (and intent) in areas like corporate social responsibility, sustainable business practices, and ethics - particularly in the set of fields commonly labeled "artificial intelligence" or "A.I." Please consider this first, imperfect attempt a conversation-starter.

Since many of us are now indefinitely desk-bound (enabled?) at home, we’re kicking off our inaugural piece with a look at sustainability implications and climate calculations around remote work.

Typically, you know a change is big when you can see it from space. And amidst all the hardships of this pandemic, some unanticipated positives have emerged: from Northern Italy to New Delhi, major drops in vehicle and industry-driven air emissions have produced clear skies and safer, less congested roads.

Nitrogen dioxide (NO2) levels throughout Italy decreased in 2020 during lockdown in response to COVID-19. Source: Space.com

But before we get to remote work, let’s talk a little about air while we’re on the topic.

Air pollution, plus its related health and respiratory consequences, is a human-made pandemic unto itself. Millions get sick and die prematurely with conditions linked to bad air each year.

To be clear, there’s no utilitarian climate versus pandemic trade-off here. Lives are lives, tragedy is tragedy, and it’s not binary. We can have cleaner air and beat COVID, both leading to better public health outcomes.

Plus, both themes are connected. Poor air quality increases a person’s risk of contracting COVID and other airborn illnesses. It also increases someone’s risk profile with the disease due to reduced lung function and greater respiratory inflammation. One U.S. study finds even a small increase in PM2.5 (for Particulate Matter, an inhalable form of particle pollution) per cubic meter is associated with an 8% increase in COVID-19 mortality rate. A second study in the Netherlands finds the correlation may be even higher.

Clear air, along with better indoor air quality and circulation, intrinsically protects us from pandemics, not to mention conditions like asthma and lung cancer. Timely and important certainly, but what does all this have to do with remote work?

The major, commonly understood sustainability or climate implication of more widespread remote work is it cancels commuting. This in turn, depending on where you live, takes cars off the road and their exhaust out of our air.

In car-abundant America, air levels of nitrogen dioxide (NO2), a principal output from car exhaust, dropped by 30% on average in air surveys around Seattle, Los Angeles, and New York City since stay-at-home orders transitioned more employees to remote work. 17% improvements have been recorded throughout cities in China, where car ownership demographics are slightly different.

However, NO2 is only one input to “air pollution” en masse. So while remote work meaningfully reduces NO2 emissions, it doesn’t necessarily change levels of PM2.5 and other ozone pollutants, which recent studies have also proved out. Even with major stay-at-home orders in cities like NYC, ozone pollution levels remained unchanged.

Part of the problem (and this is truly a core and major climate change problem) is time. Shutdowns last months. Some places never shut down at all (then usually regret it later). And even with many startups continuing work-from-home policies into 2021 (and in some cases, indefinitely), the positive emissions changes from cancelled commutes remains short-term.

We’re still surprised this isn’t more common knowledge (in fairness, maybe most of us would rather not know given the alarming implications), but carbon emissions last a long time. When carbon dioxide (CO2) is released into the atmosphere, some of it remains there for decades. 40% can last up to 100 years. Here, the youth climate strikers have it correct: carbon is, quite literally, a tax on them and future generations.

So we know more remote work (less car commuting) is good for the planet, reduces a company’s carbon footprint, and helps reduce the rate and severity of climate change.

And, if we’re going to realize the benefits of remote work, we need to commit to it long-term, not just during a pandemic.

But, we can also see only reducing car commuting is insufficient, both in overall social or economic terms, and - if you lead or work at a company with a large emissions and/or environmental footprint - at the climate or ESG strategy level within an organization.

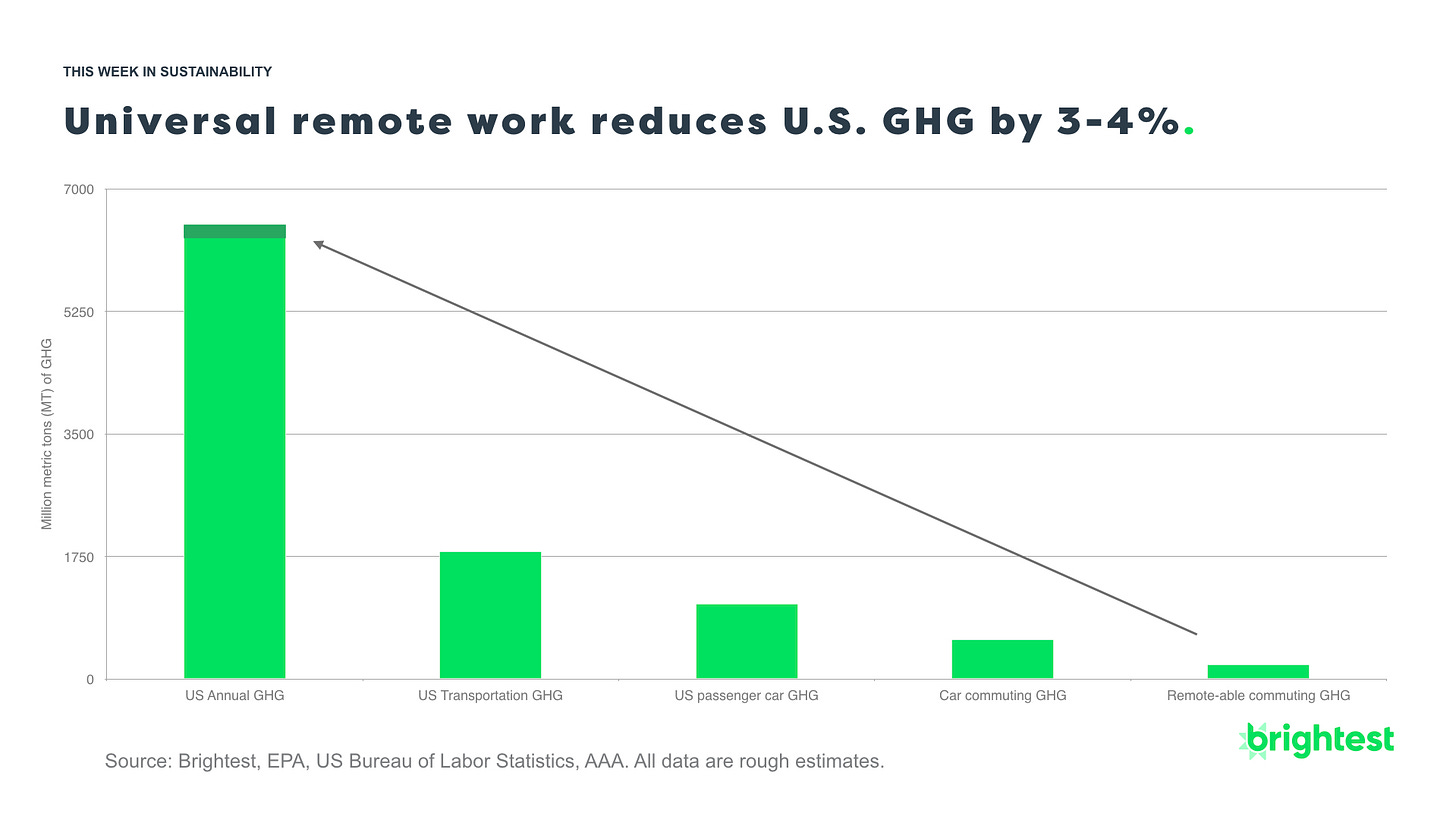

Some macro calculations help illustrate this point.

Since the U.S. EPA’s data isn’t the most reliable of late and we’re in a period of high economic uncertainty (and some contraction), we can generally estimate the United States generates somewhere around ~ 6,500 million metric tons (MT) of greenhouse gases (CO2, NO2, etc.) or GHG this year. It may end up being closer to 6,000 if we really experience economic slowdown, but (a) it doesn’t really matter for the purposes of this thought exercise, and (b) 6,000,000,000,000 metric tons of emissions is still a disastrous and unsustainable rate for any country to pollute.

Of that footprint, roughly 28% of GHG emissions come from transportation, where 59% or around 1,000 million MT comes from cars. Using driving data from the U.S. Bureau of Labor and AAA and a 52.2 minute round trip average, driven commute, 581 million MT (58%) of U.S. car emissions can directly to be linked to people driving to and from work. Driving to work then, all-in, is roughly 8-9% of the United State’s annual GHG footprint.

One other sensible adjustment to make is for the people who can work remotely. Some jobs, particularly “essential” ones like selling groceries, delivering mail, and working in hospitals can’t go digital. Here, the University of Chicago estimates up to 37% of U.S. jobs can be done virtually from home.

Taken together, if every American who can work remotely does, we’ll cut annual U.S. GHG output by ~215 million MT, or in the range of three to four percent. That’s both really good (a 3-4% drop in emissions from the world’s largest economy is a really nice start), and not nearly enough. For example, we need twice as much emissions reduction (globally) to keep global warming to 1.5° - 2° C, an important and, in many parts of the world, life-saving climate target.

We’ll stop here and disclaim this estimate is clearly imperfect. For one, a higher percentage of work that can be done remotely (technology, business administration, business services, digital creative work) may be concentrated in cities with lower rates of car ownership and usage. This is particularly true outside the U.S. in places like Amsterdam or Copenhagen [pictured above], where most commuters are already cyclists. (A recent Copenhagen visitor also shared COVID cases are sparse and well-controlled there, with office work largely proceeding normally). Public transit availability and electric vehicle adoption rates also matter.

By extension, what’s true for the economy or a country overall entails similar logic for organizations. Remote work should be part of your corporate social responsibility, social impact, or climate roadmap, but is only one tool in your toolkit. Put another way, it’s a mode of employee travel, and should be understood and measured accordingly.

And from an employee perspective, remote work and reducing work-related air travel are the single largest changes that reduces an individual team member’s carbon footprint. Laptop power, using the coffee machine, and other types of facilities resource usage don’t even come close.

Remote work also needs to be considered holistically, particularly during a pandemic. Childcare, ergonomics and posture issues, and/or mental health pressures from social isolation are all realities for many remote employees, and will continue to be into 2021. Some beyond.

A better world is possible, and many of us will continue (and increasingly) work toward it remotely, but we need to remember to use all the tools available to us for change.

This Week in Sustainability is a weekly email from Brightest (and friends) about sustainability and climate strategy. If you’ve enjoyed this piece, please consider forwarding it to a friend or teammate. If we can be helpful to you or your organization’s sustainability journey, please be in touch.